by Mark Andaman

They told me to wait outside the room. It was a dark November evening, and we were on the

sixth floor of the main teaching building. I had managed to acquire a dedicated English-study

room and it was my habit to visit it regularly in the evenings to give speaking practice to the students. I didn’t charge for this: For me it was a better way of spending the evening than trying to watch Chinese language TV, or getting sloshed in some bar, so I did get something out of this for myself. It was also neutral ground. It was also for the Marists who had taught me for no pay in Scotland.

After a few minutes they asked me to enter. The room was lit only by a series of candles, set out in the shape of a heart. They sat me on a chair at the point of the heart. Then they all sang a song for me, came up to me, thanked me for my teaching, and each gave me a small present. I was stunned. These were my Chinese students, and I will carry the memory of that evening to my last breath. If I could, I would return in a heartbeat. Chinese know when you are doing something good for them, and they show their appreciation unforgettably.

The college wanted me to go to the New Campus, and offered me the choice of some really nice new

apartments, but I thought the students I had dedicated myself to would then have no foreign teacher. So I learned my first Putonghua (Mandarin): Wo bu qu! I won’t go! And they respected that. Well, I wouldn’t go! I’d rather have returned to New Zealand.

The college was part of an odd university; one campus was set aside for those students who had

not done well at the annual College Entrance Examinations, the terrible final high school tests that can decide a student’s entire future life. They had to pay double for their study; whether they got their money’s worth is a moot point. They were not highly regarded as students, but that was not my opinion. Some have done remarkably well since leaving. Loyal to their families, they do their best.

In the typical Chinese way, foreigners, laowai, were isolated in separate accommodation, but each

small apartment was fully furnished and equipped with computer, air-conditioner, TV, DVD player, refrigerator, cooker and toilet and shower. The cooker was an electric hotplate style, very handy. There were even cooking pots. There is always a liaison teacher for all foreign teachers, usually an English teacher, who can act as assistant and “minder” for all problems. Even part of the power bill was met.

Some teachers had adjustment problems. One threw a fit at the cockroaches she inherited, but the

truth is that many foreigners do not exactly have clean living habits, and at 38 degrees and 90 per cent plus summer humidity, cleanliness is a must. Apartments were easy to keep clean, too: Chinese do not use carpets as a rule, only vinyl, and a regularmopping does the trick.

The college was in a southern province, and you might expect that means it would have warm winters.

The tomb is that of Fr Vincent Lebbe, in Chongching. Local Catholics still sing songs around his tomb even though he died in 1940.

You would be wrong. The city in which it was situated, Nanchang — known for the place where Matteo Ricci stayed in more than 400 years ago — was set in a large flat plain south of the Yangtze and, being south of the Yangtze, was deemed to be warm. Unheated classrooms and unheated dormitories at night, a precaution against fire, were the rule.

It was no surprise to see the 40 or so students in a class huddled against the windows, hoping to warm themselves in the sunshine. Yes, sunshine. The city’s pollution count, measured in 2.5 microns rather than 10, as here, was quite reasonable. Once or twice the nearby river fog would

carry an excess particulate load, but frankly it was usually just fog, not smog. Only on smoky mornings after New Year’s celebrations do you feel the need for “assisted breathing”.

The word “Chinese” is almost synonymous with “firecrackers”, and the racket of their explosions resounds till late at night, and again early in the mornings, just to remind you. They are banned in the centres of bigger cities to protect against the shattering of office window glass, so some foreigners, defeated by the annual lord-knows–how-old battle against the monster nian, retreat for safety to city centre hotels. Arriving one day at that time, I thought World War III had broken out. So amusing to see unrepaired second or third floor window glass: It’s the Chinese way. Next

year it will be another window.

Teaching contracts are controlled from Beijing, and pay is decidedly unexciting. You go because

you love teaching, and you will meet some of the politest and most welcoming students in the world. Good teachers are uncommon — I only try — and it is up to you to make the difference.

Your personal example and lifestyle are of paramount importance.

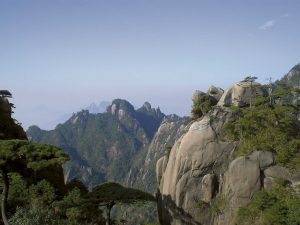

A foreign teacher in China does not have to spend all his or her time in a classroom: I have visited many cities and places of interest, from North China to Yunnan, and had many fascinating experiences, seen 1000-yearold remote cave rock carvings and truly beautiful, remote and clean country tourist locations as well as genuine and not-so-genuine antique villages. Rail travel is cheap and a great way to meet ordinary Chinese — my last lesson in China in written Putonghua

was delivered by an eight-year-old girl on a train to Shenzhen that took me on and out of China. I wish I was going the other way.

Limited for words, I can only give a tiny indication of my days in China, but I want to leave all who are kind enough to read this with the clear impression that if you go and expect little, you will receive much. It takes time: The Chinese way is to get to know you first, then you will be rewarded with trust by people you can trust. Complaints do work, but they also make enemies. Just accept what you find and remember why you’re there — for the students — and that many Chinese live in situations far worse than anything you are likely to suffer. Although poverty prevents most from leaving, you can just hop on a plane and disappear far beyond the clouds that brought you any time you like.

Believe me, with the right attitude, you’ll never want to do that.

Mark Andaman has a degree from Canterbury University and has lived in seven or eight countries. He has been a police officer (in the United Kingdom), a business manager, and was denied teaching qualifications in Christchurch on the grounds of age. He obtained an ESOL certificate in New Zealand and has taught in South Korea and China. He has many friends in those countries.

Reader Interactions