by PETER GRACE

Making assisted suicide legal will reduce our freedom, United Kingdom lecturer Dr Kevin Yuill told an audience in Auckland on May 24.

Dr Yuill spoke the day before a hearing began in Wellington into an application from brain cancer sufferer Lecretia Seales for the right to have her doctor end her life. (Lecretia Seales died on June 5.)

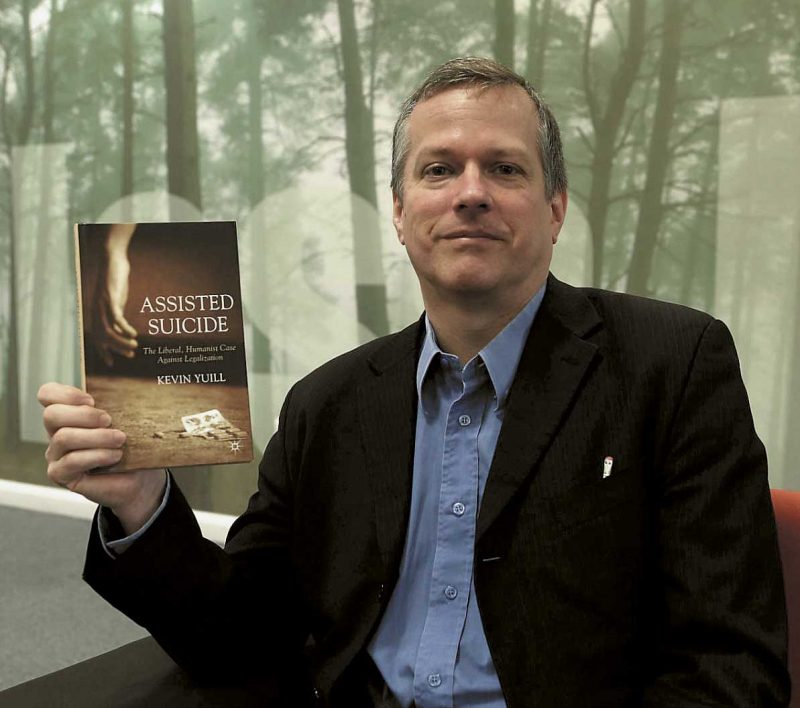

Dr Yuill describes himself as an atheist. He teaches history at the University of Sunderland, with his teaching and research interests described as diverse and interdisciplinary.

In 2013 he published Assisted Suicide: The Liberal, Humanist Case Against Legalisation.

His talk in Auckland was on the Rationalist’s Case Against the Legalisation of Suicide. There were myths surrounding assisted suicide, and he wanted to outline what those were, he said.

One myth is that it is a libertarian cause, promoted on the basis of empowering the individual. However, he said, inviting the state into areas previously private will decrease privacy. More and more we may not be able to make these decisions for ourselves but will be

reliant on the state.

“The imposition of regulations in this sphere will mean no individual choice, but that doctors will make more and more of our most intimate and private decisions.”

We should look more closely at this so-called right to die, said Dr Yuill. “It’s like talking about the right not to be affected by gravity.”

Everyone present for his talk could cause their own death, he said. One man in England had locked in syndrome and could only blink. And he wanted to die. “He refused food and drink, and died in less than the seven day cooling-off period.

“I oppose the legalisation of assisted suicide, and of compassion, trying to put it into some sort of bureaucratic structure. And I think institutionalising assisted suicide is not going to be good for essential human relationships.”

Advocates for assisted suicide say it’s about individual decision-making. But it’s not, Dr Yuill said.

“First of all, it’s about assisted suicide. It’s about having the right to ask. You can ask all you like. It’s about assisting a suicide.”

Dr Yuill said one of the things he talks about is medicalising suicide. “It’s a moral question in the end.

“Even Switzerland, even the Dignitas clinic [which exists to help people to die], regards clients as patients.

“So it doesn’t really give the individual power. It gives power to the doctors and courts.”

Advocates talk of the importance of individual autonomy. Baroness Helen Warnock of England is

strongly pro-assisted suicide, and she has said that she doesn’t think the principle of patient autonomy is a very strong ground.

“When they are selling you this message of autonomy,they step away from it pretty quickly.” In other words, he said, they want to make suicide a professional activity, “and that doesn’t sound like suicide any more. That sounds like killing.”

He thinks the right to refuse treatment is very important, Dr Yuill said. “If I don’t want you to operateon me, you should not be able to touch me. It exists as a real sort of right.”

However, he believes legalising assisted suicide will undermine that right. “It assumes

I am better off dead. If I am better off dead, it doesn’t matter how that’s achieved. It doesn’t matter how [I] die.”

In the United Kingdom there were calls for a transparent assisted-suicide process, overseen

by doctors, medical staff and lawyers.

“I am not religious,” Dr Yuill said, “but I certainly don’t want to kick out priests and replace them with lawyers.”

In Oregon, 57 of 59 such cases had a “compassionate choice volunteer”.

“Now here,” said Dr Yuill, “you would throw out the priests and have a creepy person who

is interested in watching people die!”

Freedom from state intrusion into the deathbed scene is important in several ways, he said.

For one thing, putting it into the full glare of publicity will, ironically, dissuade doctors from some natural human acts of care. One is treatment known as “double effect”.

“It’s giving enough painkiller to relieve the pain, but it also hastens death. If you shine this legal spotlight, doctors will have less room to take those compassionate actions.”

He had no doubt that if Lecretia Seales had asked for it, a doctor would have helped her.

He believed state control of assisted suicide would say it is too difficult a decision for individuals. Then, though, “there are two elements of judgment being encroached upon”.

Although we are told that some individual decisions are good, and some individual decisions are bad, by having regulated assisted suicide, “you can never have a good one”.

It also tells the rest of us not to judge.

“But we need to judge. You are a full human being like me and we have some sort of relationship.” He believes it is important to say what’s right or wrong.

That is not to say suicide is good, he said. “Most of the cases I have known have been bad and have impacted on huge numbers of people.”

He recalled someone who shot himself, and the massive impact that had on those around him. “And this is something that will forever mark their lives. And I remember thinking, this is a wrong decision.

“We can forgive him. But we can say, you took a wrong turn. And this is a moral decision, and I think we should be able to do that.”

At the same time there were “good” suicides, such as Captain Lawrence Oates, who sacrificed himself in the Antarctic in an effort to allow his companions to survive.

Reader Interactions